Showing the Meaning or Truth of Something

That's What Illustrating Does--and What Illustrations Are.

It seems fairly obvious to me that how an illustrator chooses to illustrate a verbal text is bound to affect how someone looking at the illustration is going to understand the text. According to the Cambridge dictionary, “Illustrate” means “to show the meaning or truth of something more clearly, especially by giving examples.” But if visual illustrations of written texts are attempts to show its truths, the truths the work of any one illustrator conveys tend to be different from the truths found in the work of other illustrators of the same texts.

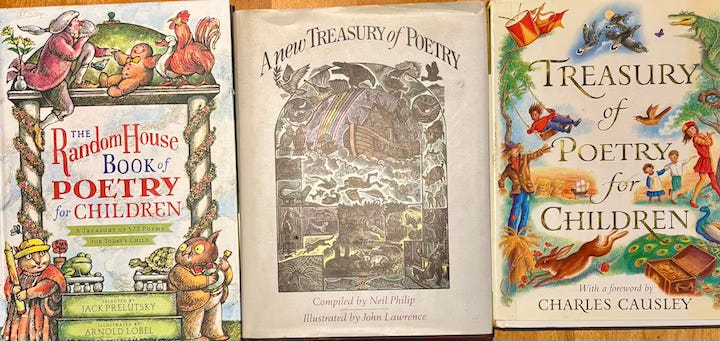

Consider, for instance, the differences between the illustrations on view in these different anthologies of poetry for children.

Merely in being present as illustrations of the poems they accompany, they all inevitably imply what poetry is, how a reader might relate to it and think about it. But as the illustration above makes clear, different anthologies offer significantly different illustrations—and therefore, surely, different ideas about poetry.

A closer look at how three quite different artists choose to present a collection for which they are the only artists reveals just how much that happens. Here are the covers of three different anthologies.

A cover illustration is especially significant in signalling readers what to expect of the book’s content before they even open it—in this case, how to think about what poetry for children is. At first glance, these three are both surprisingly different and have a surprising amount in common.

What they have in common is how they all emphasize the wide variety of things to be found inside. They convey diversity. They convey plentitude. They convey that poetry is richly enticing, like a mixed box of chocolates or a lavish display of Christmas tree ornaments. Each of them depicts a range of characters and scenes from some of the different poems to be found inside. And much as a display of different ornaments always suggests the connection to Christmas they all share and therefore, the potential connection of each of them to any of the others, each of them suggests ways in which these scenes and characters from different poems are connected to each other.

However, the ways the connection are made are different.

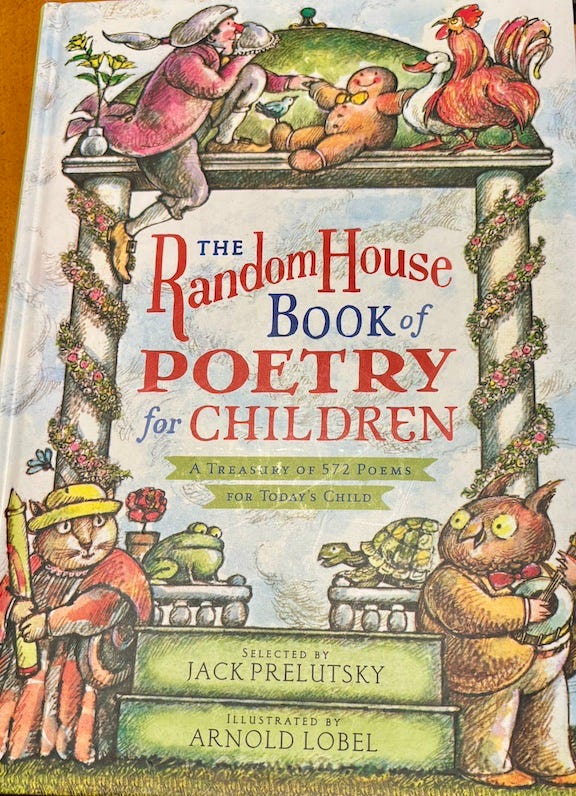

On the cover of The Random House book, Arnold Lobel depicts not only people but also objects from different poems interconnecting with each other:

The pie-eating fellow at top left seems to be holding the gingerbread man’s hand, and the cat/woman in the flowered hat at bottom left is holding a crayon that appears on its own in one of illustrations.

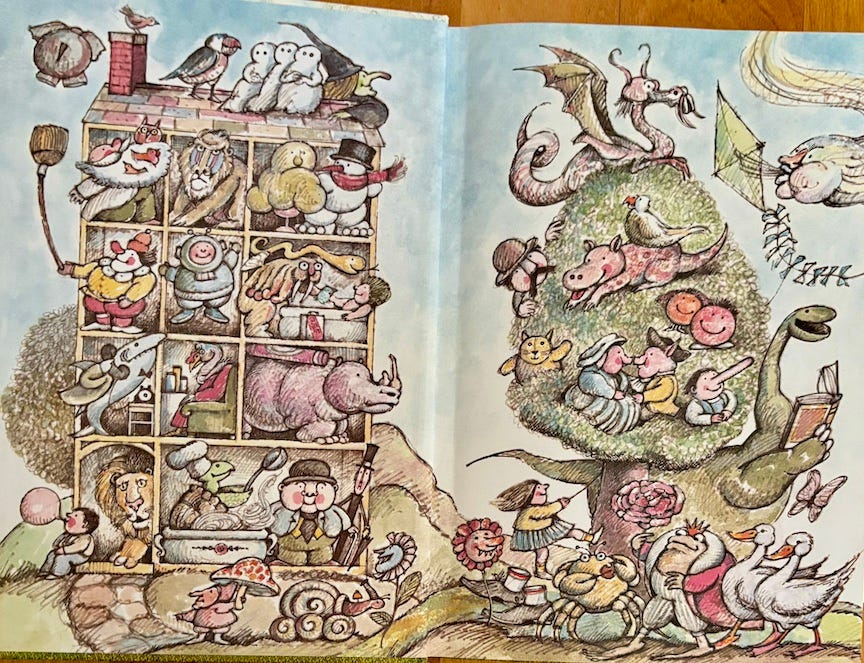

Nor are these the only characters depicted in relation to specific poems that also appear in crowd scenes. Opening the book reveals two more sizeable groups of characters on the end papers, one group filling a wall-less house on the left and another group cavorting in and around a tree on the right (which make it look a little like a decorated Christmas tree).

All the figures here can be found inside the book in connection to specific poems. Furthermore, a number of other illustrations of individual poems throughout the book offer yet more crowd scenes: crowds of mice, birds, frogs, butterflies, various animals together, fairies, commuters, and a number of crowds of children. Happy crowds throughout the book tend to celebrate poetry as a happy group activity, a social event. A party.

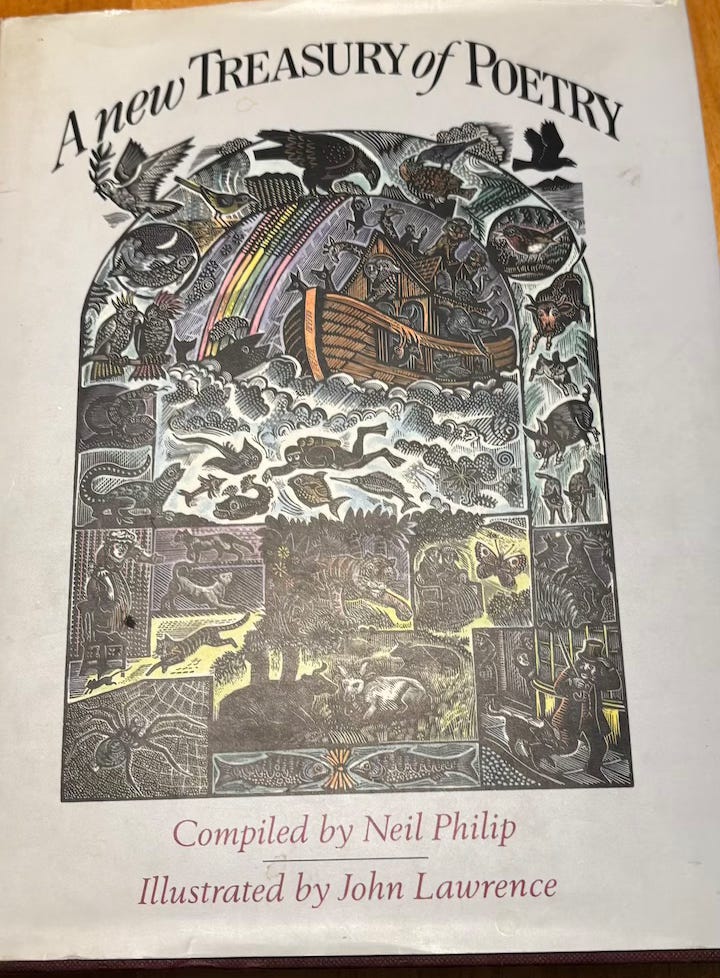

John Lawrence front cover for Philips’s New Treasury feature a central image of what appears to be Noah’s Ark under a rainbow as various animals and people head away from it and into a range of different other places.

While there is a crowd here, it consists of people fleeing from being part of the crowd. In a sense, we’re looking at the figures found in illustrations of individual poems in the process of becoming those individuals. I could view this cover as a sort of allegory of reading any poetry anthology: You start with a sense of multiplicity and gradually begin to understand how each of the pieces that make up that multiple effect has its own. special kind of interest. The confines of the crowded ark precede the creation of a whole number of different unique experiences off it.

While the connections between characters ands scenes from different poems on Diz Wallis’ cover for the Causley Treasury are more subtle, they are nevertheless connected by the way the backgrounds behind the characters share colours that connect different ones to the ones next to them.

Even so, though, there’s little sense of an actual conglomerate here. The individual figures are more disconnected and solitary than they are part of a crowd. Still, their shared presence on the cover implies their connections to each other and therefore, to what poetry is.

But while these three covers are similar in what they imply about the variety and abundance of what is inside, the differing styles of the three illustrators create a significant difference in how they invite readers to think about what poetry is.

Arnold Lobel’s illustrations for the Random House book are much more loosely drawn, in a way that makes them seem much less formal or serious. No matter what his illustrations depict, they make just about everything in them look like a lot of fun. Not only humans but also various animals are shown to be smiling whenever possible, and as I’ve said, the many crowds on view then all appear to be enjoying something very much like a party. It is a book full of parties.

There are also many visual jokes.

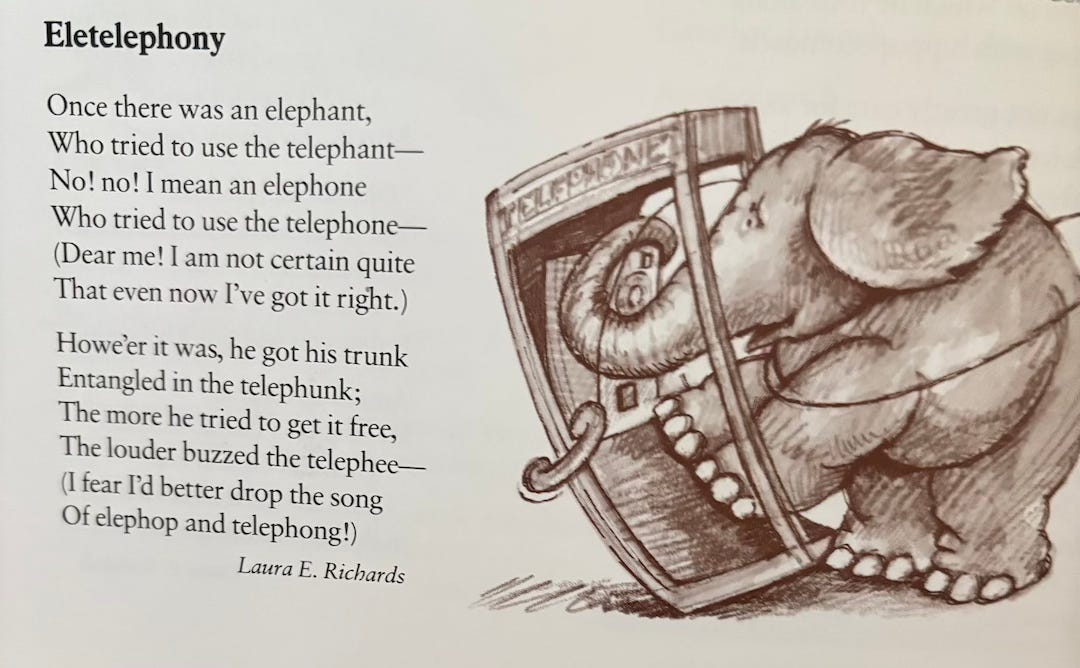

The depiction of Moses supposing his toes are roses actually shows the toes as roses

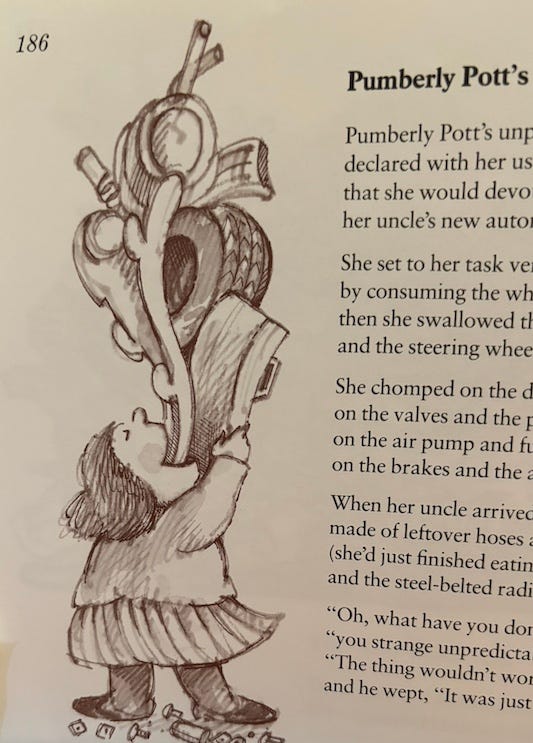

The always hungry niece of Pumberley Pott in seen the process of downing a huge stack of car parts

Emily Dickinson’s frog who tells his name “to an admiring bog” holds a sign that says “frog” while he does it.

Two turtles bathe in a soup tureen while eating bowls of soup, presumably turtle soup.

The old lady who swallows a fly in seen in a sequence of catching the things she eats that ends with a depiction of a gravestone that says “Poor Old Lady.”

One image shows a king wearing nothing but a crown and a pair of undershorts.

I hasten to note that every one of these visual jokes is a more or less accurate depiction of what the poem it accompanies describes. This is an anthology utterly determined to offer lots of fun, lots of jokes, lots of opportunities to laugh and to smile just as the various humans and animals depicted so often do. And the illustrations happily confirm that.

Lawrence’s illustrations for the Philips anthology are an entirely different matter.

They look something like the engravings often found in books published in earlier times, with much use of hatching and crosshatching--an impression confirmed by the absence of any colour anywhere but on the cover. Almost all of the depictions of people confirm the sense of past times by seem to imply, if vaguely, historic clothing styles. They seem to be of the past, but from no specific past era.

But despite the original impression of complexity all that seems to create, these images are in fact quite simple cartoons, most of them depicting just one or two figures but at a scale small enough to draw attention away from the minimal faces of those figures. They then seem to be mainly decorative, but in a way the imposes an air of respectable antiquity on the poems they accompany. Personally, I quite like them—but I wonder how a publisher would choose something so unconventionally childlike for a collection of children’s poems. They make the book seem somehow elegant, tasteful, important, serious, and costly —all the qualities we usually assume children haven’t got around to being or caring about yet.

I’ve left the illustrations by Diz Wallis for the Causley/Gibbs Treasury for last because—well, to be honest, I don’t know quite what to say about them.

I don’t know quite what to say simply because these images seem so—well, so bland, so expectable. They are so absolutely conventional that they are clearly intended to be illustrations of texts with children in their audience. But beyond that, and unlike the illustrations by Lobel and Lawrence, they give me no sense of what might be distinctive or special about those texts. They might just as easily appear attached to poems or fairy tales or descriptions of toys or children’s clothes on sale in a catalogue. In all three cases, they would probably do a pretty go job both of expressing the main meaning of the text and of doing so in a way that conveyed childlikeness and so identified the text as being concerned with and possibly for children. But they would do so without conveying anything in the way of the texts’ more specific meanings or truths.