At first glance, Gyo Fujikawa’s A Child Book of Poems seems to be nothing like the “dazzling foray into word and image” that Sullivan’s Imaginary Gardens offers. It is anything but dazzling, primarily because the illustrations of a fairly wide range of poems are all by the same artist and all in more or less the same style. If the range of different artworks in Imaginary Gardens creates an almost anarchic atmosphere of random variation, the illustrations in A Child’s Book of Poems not only offer a comforting consistency, but what they consistently are is gentle, charmingly and unthreateningly adorable.

Fujikawa had as highly successful career as an illustrator of children’s books in much the same style. According to Wikipedia,

A prolific creator of more than 50 books for children, her work is regularly in reprint and has been translated into 17 languages and published in 22 countries. Her most popular books, Babies and Baby Animals, have sold over 1.7 million copies in the U.S

Furthermore, that style it itself undazzling, a pleasant depiction of primarily happy people in primarily happy places:

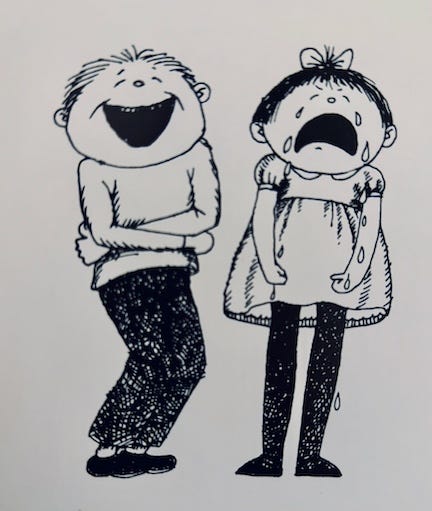

Her most popular books, Babies, Baby Animals, A to Z Picture Book and Oh!, What A Busy Day!, unfailingly represent a happy, detailed version of childhood. Her joyous illustrations remain sweet and nostalgic, without ever becoming overly saccharine. Her paintings of children are recognizable for round happy faces, rosy cheeks and simple dot eyes.

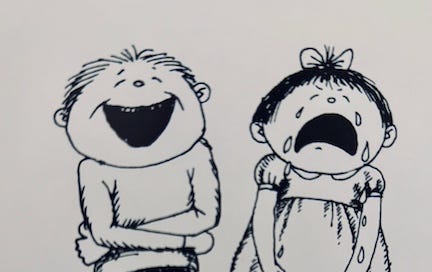

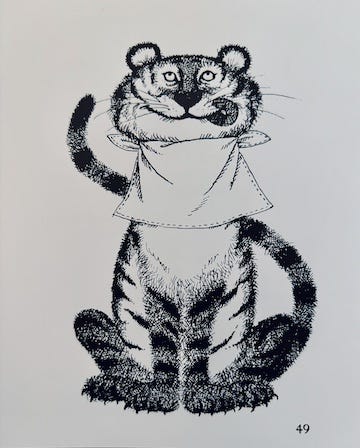

Even when the images depict children crying or a tiger licking his lips after a meal of young lady, they do so in comical cartoons that downplay the sadness and danger.

Even so, there are far more illustrations depicting happy moments—smiling children (and animals) greatly outnumber sadder ones. According to Sara Larson in a New Yorker article,

As a child, I knew that seeing her name on a book cover meant feeling connected to the page, being transported—by joy, cheerful fellow-feeling, occasional stormy moods and skies, and a hint of nursery-rhyme dreaminess. I associated her giant-sun image with the bounding pleasures of a favorite song, “Free to Be . . . You and Me.” Its opening banjo and this yellow sun both led to a land “where the children are free.”

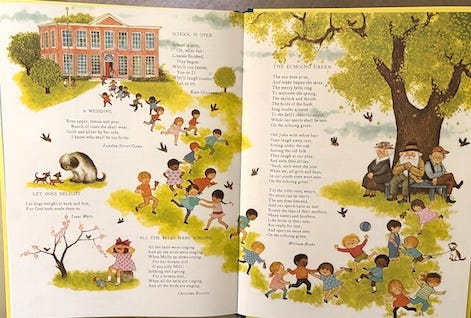

Children also seriously outnumber older people in these illustrations. There are only about twenty-five adults depicted throughout the book, and of those twenty-five, three are mothers with young children on their laps and six others appear in one small image of a king and his councillors. Meanwhile, one double-age spread that offers one large illustration to accompany five different poems includes well over thirty children at play, being observed by just three older people. They join the many children depicted throughout the book.

Often, furthermore, Fujikawa chooses to illustrate poems that are not necessarily about children with figures of children. She often includes young boys and girls in her illustrations of poems that don’t mention the presence of any people: Blake’s “Night,”Longfellow’s “The Village Blacksmith,” Wordsworth’s “Daffodils,” Christina Rossetti’s “Oh Fair to See”; and her illustration for Sara Coleridge’s “Seasons” depicts a different child for each month.

The consistent impression of an overall vision that unites the book clearly implies that the poems they accompany share that vision—that even the old-fashioned clothing and settings Fujikawa provides for fairy-tale-like poems or anything that affirms an historic setting are being seen in the same good-humoured and consistently utopian point of view. The clothes change. The round happy faces do not. Even many of the animals depicted, including the fish entering the “gently smiling jaws” of LewisCarroll’s crocodile look happy. Many of them even appear to be smiling.

But meanwhile, while the poems these illustrations accompany tend to represent the relatively narrow range of possible styles and subject that I’ve come to identify as typical of children’s poetry anthologies, they are nevertheless diverse in subject and in style—more diverse at least, than the illustrations are, in a way that the illustrations then tend to downplay. In a way then, the illustrations make this unquestionably “a child’s book of poems:” by misrepresenting them—ignoring their less childlike, i.e., less joyful and innocent qualities.